Elisa Frasson about laborgras

Elisa Frasson about laborgras

laborgras: a Never-Ending Research

Last November (2021), I had the chance to see and write about laborgras’ piece “sinnestaumel”, which premiered at St. Elisabeth Church (Berlin Mitte) and was based on J. S. Bach’s Six Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord, BMV 1014-1019.

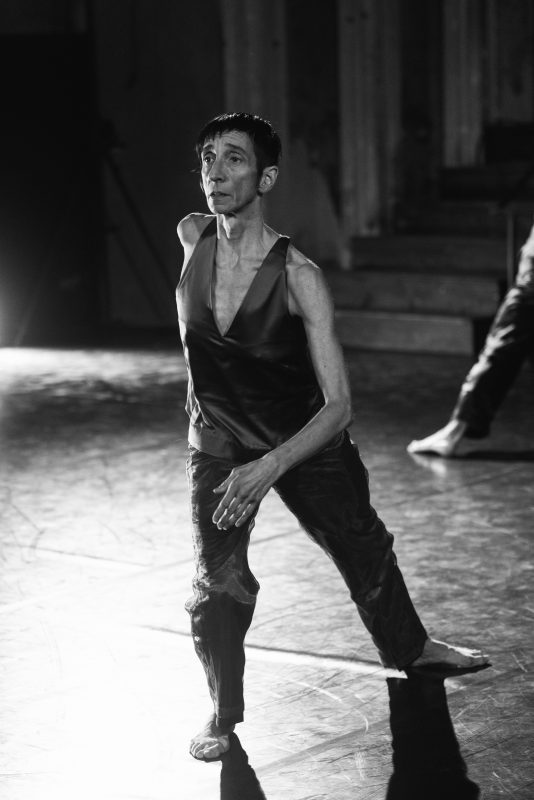

Recalling my review at that time, and my memories of the piece, I still clearly feel the extent to which the “movement of the dancers were altering my perception of the space — through their very clear and conscious writing of the body in the space. Their bodily awareness and accuracy allow me to perceive, for example, the precise position of a hand on a scapula before a lift, or the delicate yet rigorous movement of fingers cutting through the air” (Frasson 2021). Their rich and articulate movement language comprises “shifting weight, spiraling of the body, rapid body transfers in the space, walking, and complex movement patterns which echo from dancer to dancer” (Frasson 2021). In that choreographic score, I perceived a structured and embodied language through which the dancers could engrave the space with their bodies. The unique quality of the gestures revealed how much the political agenda of a moving body could express by itself, in acknowledging the movement research as a source of empowerment for the senses and our perception, both as performers and audience members.

Since 2021, laborgras has been working with Baroque music, developing a consistent practice of sensing it, writing with their bodies through the music score. First with “Das Fest” (2021), set to Handel’s music, then “sinnestaumel” with Bach, and now an upcoming project using Monteverdi. Their choice of Baroque music is derived from a dual consideration: on one side, this music was written for dance, and on the other, Baroque art is freeing the form.

More recently, in May 2022, I had a thought-provoking discussion with the artistic duo. We talked about their lives, training, sources of inspiration and creative paths, delving into issues such as visual arts, physical research, movement awareness, agency as artists in a city like Berlin, responsibility as artists and educators, their genealogy, Trisha Brown, the years in New York, collaborations, and friendships in the dance field, to make a brief summary of our conversation. Furthermore, I had the opportunity to go through their journals, sketchbooks, and their massive library.

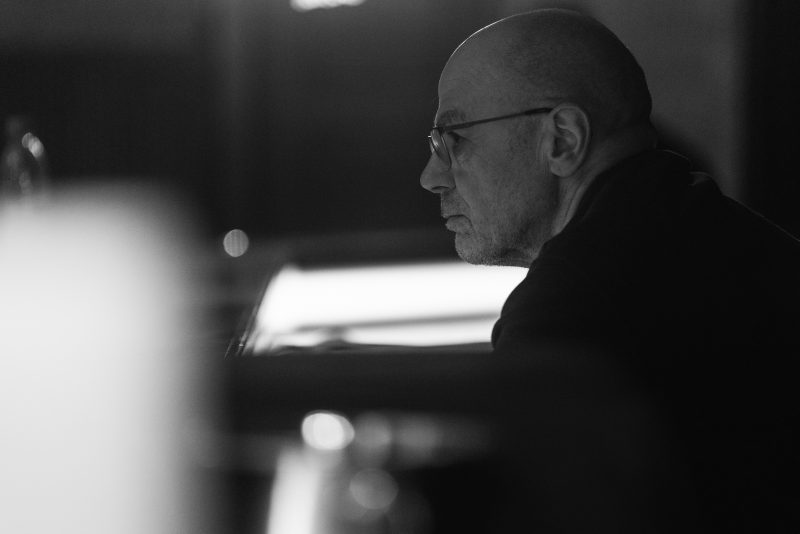

After a few years researching and working in Hamburg, laborgras resettled permanently in Berlin in 2002, in an open space — a former mechanical workshop — created to address their practice-research together with various artists, movement researchers working with and through choreography and dramaturgy. During these first 20 years, co-founders Renate Graziadei and Arthur Stäldi intentionally and intensively created the conditions for their work and practices, laying the foundations for nourishing various kinds of creative encounters.

At the heart of their creative work there is the research and curiosity to discover movements, following specific movement logics able to transport a certain kind of feeling or sensation (Graziadei et al). They continuously question how the relationship between gesture and the physical body shapes the choreography. How is the attention directed to and between movements? What happens when this other space emerges? Where and how do the question marks emerge in the work? During our meeting, I was impressed by Renate and Arthur’s precise and clear movements when they demonstrated a gesture. While they were tracking the forearm, explaining how it is related to the shoulder via the elbow, I clearly noticed the scapula sliding in the upper back and linking the space between the arm and the spine. How long does it take to establish these inner bodily bridges in an outside form?

Right from the start of choosing their project name, their intention was clear and set. laborgras has its root in the word “labor”, as a laboratory, a place to experiment with something physical not only artistically but also through teaching ‘open classes’ dedicated to anybody who has an interest in moving research. Originally the name was “laborgras 888”, where the 8 stood for infinity, thus for research — in movement and dramaturgy — that could continue without end. At the same time, their homonymous studio operates as “a forum for artists, a production and performance venue for contemporary dance” (laborgras 2022) and is internationally well-known. It is founded in researching ideas through dance and choreography that productively embodies and stimulates creative and critical discourses in the field of theatrical and dramaturgical composition.

laborgras also positions itself as a place that generates conversations with other practices, such as lighting, costume design and video art, trying to reach a Gesamtkunstwerk. Such collaborations are fundamental to making the studio an artistic and interdisciplinary community. Since the end of the 1990s, they have been creating specific cutting-edge video projects for the stage. In “Melting Point”, their first work specially conceived for the studio’s Berlin opening in 2002, they explored virtual spaces through video installations and real time movement improvisation. One of the main questions at that time was: how is it possible to create a (virtual) and non-existing space when you are not in the same place? laborgras tries to maintain the artistic independence of the costume designer and the lighting technician, leaving them united by the joint project.

What if there could be an openness in the way artistic research is conceived beyond normative boundaries of participation, humanity, and audiences? Somehow, by the duo’s very existence in their Kreuzberg space, laborgras is questioning the acceptance of different kinds of external collaborative influences not determined by the production rhythms typical to the neo-liberal world.

Their movement research-driven choreography is based on a corporealized body-mind preparation that interacts with relational and collaborative processes. A peculiar aspect of laborgras is that they search for a direct and eloquent relationship with the audience, incorporating it in their creative process. “The public is not a recipient, rather a producer and therefore an active participant” (laborgras 2022). The sense of having an audience makes them question the way they create. In this light, the beginning of their 20th anniversary in June 2022 starts with the 2019 piece “Er…Sie..und anderen Geschichten”, based on the concept of relationship. Specially designed for the studio, it invites the audience to actively participate, to physically follow the two performers inside different studio spots. The public can actively explore and embody the laborgras studio. In this way, “Er…Sie.. und anderen Geschichten” gives viewers the opportunity to choreographically cohabitate the laborgras space, further exploring the boundaries of a never-ending moving and choreographic research.

This short writing serves as an introduction to a booklet about laborgras’ artistic research that will be edited in late 2022. It will encompass personal interviews, and the outcomes of field research and shared time within the studio, along with performance analysis framed within today’s perspective.

References:

laborgras (2022), laborgras, available at https://www.laborgras.com/ [24.05.2022].

Graziadei, Renate; Stäldi, Arthur; Frasson, Elisa (2022), Unpublished Conversation.

Frasson, Elisa (2021), “sinnestaumel”, an Expanded Dialogue Through the Echoing of the Senses, Tanzschreiber, available at https://tanzschreiber.de/en/sinnestaumel-an-expanded-dialogue-through-the-echoing-of-the-senses/ [25.05.2022].

Pictures: Claude Hofer